War crimes and the sanctity of the rule of law – PART I

Share the post "War crimes and the sanctity of the rule of law – PART I"

Hereafter follows Part I of a two-part essay titled War crimes and the sanctity of the rule of law – the trial of Lieutenants Harry ‘Breaker’ Morant, Peter Handcock and George Witton – Relevance to ADF War Crimes Investigation

By James Unkles

“It does no good to act without the fullest inquiry and strictly on legal lines. A hasty judgment creates a martyr and unless military law is strictly followed, a sense of injustice having been done is the result.” (1) Lord Kitchener cable sent to Secretary of State on 6 April 1902 aptly summarises the case for review in the Breaker Morant controversy.

“They were treated monstrously. Certainly by today’s standards they were not given any of the human rights that international treaties require men facing the death penalty be given. But even by the standards of 1902 they were treated improperly, unlawfully.“ (2) Geoffrey Robertson QC, International Jurist and Human Rights advocate, 2013 interview with James Unkles.

Australians have genuine regard and respect for their defence forces and allegations of war crimes are confronting.

However, an equal injustice and affront to Australia’s values enshrined in our democratic institutions and judicial independence is an abrogation of due legal process for political and other agendas.

Leo D’Angelo Fisher’s insightful article (3) on alleged ADF war crimes and its reflection on the failure of leadership in the ADF presents an opportunity to balance the assessment of allegations of war crimes with the significance of the preservation and promotion of the rule of law in ensuring those accused are given the presumption of innocence, proof beyond reasonable doubt and treated in accordance with common and statutory law.

Nothing less is unacceptable in a civilised society.

Leo D’Angelo Fisher rightly draws comment on the trial of Lieutenants Harry ‘Breaker’ Morant, Peter Hancock and George Witton, three Australian volunteers arrested, tried and sentenced for alleged war crimes during the Anglo Boer War of 1902.

This controversial aspect of Australian military and legal history is also significant as it illustrates that the prosecution of alleged war crimes then and now can be polluted by another injustice, trial and sentencing not in strict accordance with the law and due process.

Because there has never been any doubt that Morant, Handcock and Witten were involved in the shooting of prisoners – accusations they admitted to – the debate has focused entirely on the question of whether orders to that effect were given.

No-one has objectively looked at the legality of the trial proceedings and whether the rule of law and trial procedures of the law of 1902 were meticulously adhered to or ignored to achieve a politically inspired outcome.

The war between the British and two Dutch South African republics (the Anglo Boer War) began on 11 October 1899 and lasted until 31 May 1902 when a peace treaty was signed.

The bitter conflict that raged across the South African veldt was a war between the Boer population on one side and the might of the British Empire, keen to secure for itself the wealth of colonialism, gold and a strategic geographic location on the African continent.

Britain was determined to win the war, but failed to produce a decisive victory against a formidable insurgency.

Finally, in order to settle the conflict, the Commander In Chief of the British Army Lord Kitchener instigated brutal strategies to break Boer resistance and to fight an effective opponent.

He introduced a scorched-earth policy of burning farms and crops, confiscating and destroying livestock and imprisoning non-combatants, women and children in concentration camps to remove them from the field, thus preventing logistic support and psychological comfort to Boer fighters.

These policies were designed to strip the Boers of their resources and to break their will.

Excesses in war and the brutal treatment of prisoners are synonymous with the history of human conflict and this war was no exception.

Incidents of brutality, including summary executions, occurred on both sides of the conflict.

Lord Kitchener was desperate to end a war that had become politically and economically unpopular in Britain and he turned to Australian volunteers to fight a guerrilla war – men who could ride and shoot like the Boers and live off the land.

The Bushveldt Carbineers was a unit that played the Boers at their own game and was very successful in combat.

However, it was the use of summary executions to extract reprisals against Boers that resulted in an incident that still reverberates to this day – the arrest, trial and sentencing of three Australian volunteers, Lieutenants Morant, Handcock and Witton for shooting 12 Boer prisoners.

The three Army volunteers claimed they had acted in good faith in following the orders of their British superiors, in particular Lord Kitchener.

Morant and Handcock were executed on 27 February 1902 and Witton’s death sentence was commuted to life imprisonment, but, he was released in 1904 following a determined campaign for his freedom led by the Australian government, British MPs including Winston Churchill, and his lawyer Isaac Isaacs KC, MP, (who eventually became Governor-General and Chief Justice of the High Court).

A feature of the campaign was a petition authored by Isaacs and signed by 80,000 Australians.

Critics of the accused say they were lawfully convicted of serious war crimes and deserved the sentences they received.

However, the descendants of these men and others insist that Morant, Handcock and Witton were scapegoats for the crimes of their British superiors while their British counterparts were not prosecuted for similar offences.

It is also alleged that Lord Kitchener conspired to deny the men fair trials according to the laws of 1902 and deliberately kept the proceedings from the Australian government to avoid any interference in the trial and sentencing processes.

While the men admitted to shooting Boer prisoners, they had a right to be tried strictly in accordance with the laws of 1902 and to exercise their right of appeal.

In 2009, I commenced a review of the trials and sentences of these men and completed a detailed analysis, in which I uncovered new evidence of orders to take no prisoners, the use of the customary law of reprisal to extract revenge against Boer fighters and serious procedural errors made in the investigation, court martial and sentencing of the accused.

Of particular concern was the denial of the accused’s right of appeal to the British Crown, the conflict of interest of Lord Kitchener in issuing orders to take no prisoners, while being implicated as a potential defence witness and confirming the sentences of death against the accused.

Evidence also suggests that he misled senior Crown officers and the Secretary of State for War, William St John Brodrick, by failing to detail recommendations for mercy made by the trying officers and failing to provide the Crown with a complete set of the trial transcripts as required by law.

Lord Kitchener also acted oppressively by absenting himself once he had confirmed the death sentences, thereby denying the men an appeal to the Crown.

I also focused on the writings of the Australian solicitor from Tenterfeld, Major James Francis Thomas, who inadvertently found himself the centre of this controversy when he was asked to defend the accused.

Major Thomas was given only one day to prepare the defence of the accused of serious charges tried over a period of about one month.

While the prosecution had three months to prepare its cases and unlimited resources to assist in their preparation, Major Thomas had no such assistance, had to act as both solicitor and counsel, and was refused an adjournment so he could better prepare a proper defence.

He was also denied the use of the telegraph to seek assistance from the Australian government.

The proceedings were conducted in utmost secrecy and Lord Kitchener prohibited any contact between the accused, Major Thomas, their relatives and the Australian government.

Major Thomas protested the innocence of his clients following the execution of Morant and Handcock and waged a campaign in Australia for an inquiry into the cases.

Major Thomas’ writings provided me with significant detail of how he and his clients were treated by the British military and why he thought his clients had been singled out for prosecution in deference to British soldiers.

He also complained that Lord Kitchener had deliberately absented himself to deny him an opportunity to lodge an appeal in the few hours before the execution of his clients.

Another source of evidence came from a book published by Witton in 1907 – Scapegoats of the Empire, The true story of Breaker Morant’s Bushveldt Carbineers – which provides a firsthand account of the circumstances of the shootings and the trials that followed.

I have used extracts of the transcripts of the trials quoted in the book to assist with the case for judicial review.

These men were not tried in accordance with military law and procedure of 1902 and suffered great injustice as a result.

The convictions were unsafe and the sentences illegal as appeal was denied and due process seriously compromised.

Part II of this essay is published here

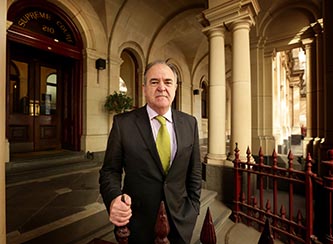

James Unkles

James Unkles

is a civilian lawyer, military reserve legal officer (Rtd), petitioner for the descendants and author of Ready, Aim, Fire: Major James Francis—The Fourth Victim In the Execution of Harry ‘Breaker’ Morant – Sid Harta Publishers, available online at Booktopia or by contacting the author via jamesunkles@hotmail.com

Please also visit www.breakermorant.com

.

.

REFERENCES:

-

- Lord Kitchener cable sent to Secretary of State on 6 April 1902 aptly summarises the case for review in the Breaker Morant controversy.

- Geoffrey Robertson QC, International Jurist and Human Rights advocate, 2013 interview with James Unkles.

- Leo D’Angelo Fisher, War-crime allegations are confronting but they may lead to welcome reforms, Australian Veteran News, 7 June 2020.

- Witton, George, Scapegoats of the Empire, Angus and Robertson, 1982.

- Greg Hunt, interview with James Unkles 2013.

- Sir Laurence Street AC, KCMG, KStJ, QC, interview with James Unkles 2013.

- Tim Fischer, AC, extract of interview with James Unkles 2013.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Share the post "War crimes and the sanctity of the rule of law – PART I"