The Message from the Grave

.

It is generally accepted in life that under normal circumstances, children pay their last respects to their parents when they pass away, not the other way around. During the 1914-18 war, sixty-two million men and teenage boys from various nations of Europe and from many continents around the globe were drawn into the conflict on land, sea and air. Eight million died fighting for their respective causes. Those at home who mourned the loss of a loved one on the battlefield may have drawn some consolation from the knowledge that they at least knew where their loved one had been laid to rest with a proper burial and service. But what if the son, lover or husband had no known grave? There was no closure for those who grieved, leaving them with a lifelong void.

On Thursday, 22 June 1916, Richard Moffat enlisted in the Australian Imperial Forces at the Brunswick drill hall, in a suburb of Melbourne, Australia. Being under the age of enlistment, one his parents had to be there to give their consent. Once the enlistment papers were signed and a health check carried out, he became Private Richard John Moffat, serial no 2698 and after initial training, joined the 58th Battalion on the Western Front in France. The Australians who served in the First World War were all volunteers; the vast majority were neither professional soldiers nor fully trained military men. In the main, they were ordinary workingmen from all walks of life, fighting alongside thousands of teenage boys not long out of school. Many women also answered the call; a job had to be done and they all pitched in.

By early 1917, the 58th had participated in the advance that followed the German retreat to the Hindenburg Line, but was spared from any assaults. The battalion did, however, defend gains made during the second Battle of Bullecourt between 9 and 12 May. On 11 May Richard was seriously wounded and was, after a brief period in hospital at Etaples, transferred via Calais and Dover to a hospital in the London suburb of Epsom. As his recovery progressed, he was granted a short furlough before receiving further treatment and rehabilitation at Uxbridge. Finally, in preparation for his return to the front, he was sent to the training and hospital camp at Hurdcott to regain fighting fitness. Richard had been absent from his battalion for three and a half months.

On 9th August 1918, during the second day of the Battle of Amiens, nineteen-year-old Private Moffat was killed in action. At the time of his demise, arrangements for the burial of those killed on the battlefield would have had to be made promptly because on the following morning, the battalion was to retire to a rest area not far from Amiens.

In Richard’s Army service file, there is a simple notation dated August 1918 which reads; ‘Next of Kin advised KIA’ but how that notification was communicated to his parents is not mentioned. Neither was the cause of death or where their only son had been laid to rest. What had been the circumstances of his burial? Did he have a grave and if so, was it a dignified burial? For his mother and father, these normal questions remained unanswered for a further eight years before they could find the peace they craved. Would they ever learn what had become of their only boy?

On a soldier’s death, it was standard Army practice for any personal possessions to be returned to the next of kin. All Commanding Officers received copies of the ‘Procedures and Rules for Burials’ as they evolved and improved. However, the practicalities quite often made adhering to the rules a matter of making a best effort according to the circumstances.

The basic instructions were as follows;

Remove nothing from the dead until placed in the grave.

Bury British, French, and German dead separately.

Bury Officers with men.

Select an unexposed position.

Enter particulars as body placed in grave.

Mark flanks of graves with posts, and wire if available.

Enter map reference and nearest landmark in notebook.

Tie up all personal belongings with identity card, place in envelope, and write particulars on outside.

Mark all graves with peg and disc and enter serial number in book.

With regards to identity discs, Army Order 287 (1916) directed that all officers and soldiers on active service wear two discs about the neck. Failure to do so was regarded as a breach of discipline. ‘Disc, Identity, No. 1, Green, will not be removed but will be buried with the body. Disc, Identity, No.2, Red will be removed to ensure proper notification of death.’

Simple though the system seemed, the circumstances on the battlefield led to errors, and frequently both discs were removed from the body and sent to the Adjutant General. Disc No. 2 did its job of notification, but the body could not then be identified when exhumed for reburial unless some information remained on a grave marker or makeshift cross. In many instances, the Green identity disc was removed and placed in a slot in the burial peg, the intention being to make identification of the body in the grave simpler. However, this frequently frustrated the purpose for which the Green disc tag was intended as the pegs themselves were often destroyed by subsequent shelling, and the body, if ever recovered, could not be identified. Some identification discs that were recovered were returned to parents along with other personal effects, Richard Moffat’s parents never received any of Richard’s personal belongings.

Under normal circumstances, units were responsible for burying their own dead, but some units had such high casualty rates that it was beyond the capacity of the survivors. For obvious reasons, it was suggested that burial parties should not be detailed to units which were about to go into action. In many cases the bodies of soldiers killed in action had to be buried during short lulls in the battle. In these brief breaks burial parties were sent out with the unpleasant task of retrieving the dead, identifying them, digging graves, and erecting crosses so that if possible, a chaplain could conduct a service before enemy shelling recommenced.

The Battalions were responsible for obtaining the information about the locations of field burials and for recording them as Burial Reports on the Casualty and Service Forms. This information would be vital in locating individual soldier’s graves after the war. Given the conditions under which field burials were often carried out, with multiple field burials taking place under the most difficult circumstances, the army did its best to accurately record details of burial sites. However, errors were sometimes made in transferring information from the field to the official records.

In July 1926, Richard and Elizabeth Moffat received one final communication from the A.I.F stating that their son’s grave had been found. A farmer had discovered an unmarked grave early that year in a wheat field on the outskirts of Harbonniéres, not far from the town’s railway station. The farmer may have brought his discovery to the attention of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission who, in due course, opened the grave. During the process of exhumation, an item was recovered which positively identified the remains as those of Private. R. J. Moffat, 2698. Finally, he could now be given a dignified burial, and his parents would at last be informed of his final resting place. The letter from the A.I.F. dated 14th July was addressed to Richard’s father, would have been completely unexpected, and considering its contents, its tone, whilst respectful, was rather impersonal. Importantly though, it told them what they would have long yearned to know – that their son’s grave had been found and he had been laid to rest at the A.I.F. Burial Ground, in Grass Lane near the village of Flers – Plot 16, Row E, Grave 12 “with every measure of care and reverence”.

However, they were never informed of the item that had allowed their son’s positive identification because on the Effects Item Form, it had erroneously been described as a ‘disc.’ They were to remain unaware for the rest of their lives that this item of personal importance was placed in the Government archives and would be forgotten for eighty-five years

From the Allied perspective, men who died on the Western Front lie buried in the multitude of War Cemeteries of France and Belgium, while impressive monuments to the missing commemorate the thousands whose remains were never found at all. Thanks to the chance discovery by the French farmer, Private Richard Moffat had at last, a final resting place. However, his story continues due to the curiosity and tenacity of two people, Deirdre and John Meredith. Private Richard Moffat was Deirdre’s mother’s only brother. They had begun in 2011, some research into Richard Moffat’s military service.

The Effects Form gives the trench map reference at which Richard was found as 62D W 12 d 5.4. which placed his grave in a field on the eastern outskirts of the village, about 150 yards from Harbonniére’s railway station. At the time of the battle, it was in the hands of the Germans and very heavily defended. This ground, already very much disturbed by the huge trench system of the Old Amiens Outer Defence Line, was further churned up by artillery bombardment on 9 and 10 of August.

An aerial photograph of the area taken a few months earlier indicates that the grave site is among the trenches of the Old Amiens Outer Defence Line, and under the circumstances on the 9th August it may have been expedient for the burial party to use an unused section of the old trench system for his grave. This was not an uncommon practice.

During their research, the Meredith’s were curious as to how the body was positively identified as that of Private Richard Moffat. The only item recovered from the grave was described on the Effects Form as a ‘disc’, so they initially assumed that it must have been an Army issue identification disc carrying Richard’s name and details. In due course, it was discovered that although this ‘disc’ was the item used as the means of identification, it was not an Army identity disc. In fact, it was not a disc at all, but Richard’s personal possession, one that should have been returned to his parents but never was.

A small handmade brass plate, about the size of a man’s wristwatch and made in the shape of Australia was inscribed No-2698. R.J. Moffat. 58th ßattn. A.I.F. This little brass plate identified him long after his standard Green Army issued identity disc had disappeared. Without it, his remains would have remained unidentified, and would have resulted in his being interred in the Military Cemetery at Villers -Bretonneux beneath a headstone reading, “A Soldier of the Great War – Known unto God.” He would have been forever ‘missing,’ and his name inscribed on the Memorial to the Missing at Villers-Bretonneux. His parents would never have known that their son had been found!

Before he enlisted, Richard had gained experience working with non-ferrous metals. He was able to hand-make his little keepsake from a small piece of brass plate, or possibly, since it is stamped EPNS [Electro Plated Nickel Silver]. Richard had been wounded and was in hospital, the second that he was improving, and the third at the end of August 1917, that he was convalescing. The next letter they received was the ‘Killed in Action’ notification. It is not known if the disc was made before or during his stay in hospital.

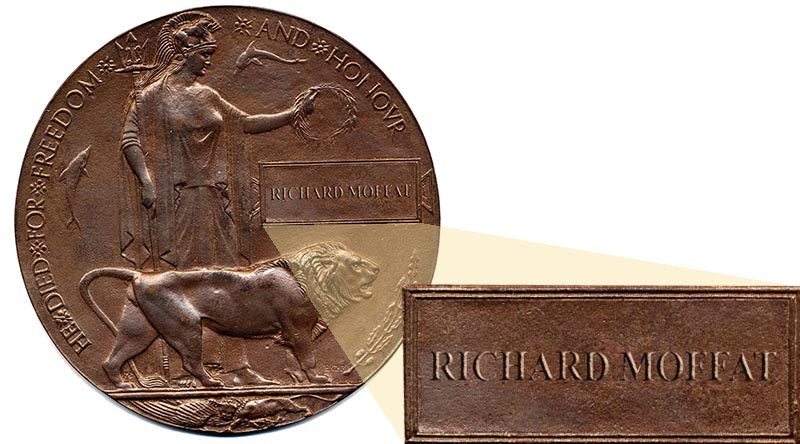

The appropriate medals were duly delivered including the bronze plaque [known as the Dead Man’s Penny] with the accompanying Scroll and King’s letter.

For any personal possessions of the fallen, there was a simple and well-established procedure as previously mentioned. Any items were to be gathered together and passed to the Adjutant who would arrange for them to be “sent on” to the Next of Kin as required by Law under the Deceased Soldier’s Estates Act, 1918 which is still in force today. Other men of the 58th Battalion killed in action on the same day had personal possessions duly sent home including such varied possessions as a silver cigarette case, a ring, a metal chain, a wallet, two hair combs, buttons, badges, a pipe stem, a religious medallion, a metal brooch, a sleeve link and the lists go on. Six of those families even received Army issued identity discs, which, strictly speaking, are not personal possessions. Under this act, the disc should have been returned to the Moffat family. Instead, it was swallowed up by the Army’s administration system and remained forgotten.

This was an object, which neither the Army nor the Archives had any right to retain by law. In mid-December 2011, Deirdre, as the representative of the Moffat family, wrote a letter to the Minister for Veterans Affairs. This was the start of an almost two and a half year David and Goliath war of words with claims and counter claims and legal fees between Richard’s descendant Deirdre and her husband John Meredith and various Governmental agencies involved. Leaving aside the question of morality, it was to be a completely unnecessary and bitter fight as the Deceased Soldiers Estate Act was simple and straightforward legally. The disc belonged to the soldier’s relative, of that there was no doubt, but the government fought the Meredith’s as they were determined to retain the disc. Why they expended so much effort to retain this particular item is not known.

Finally, the Meredith’s dogged perseverance paid off. On 3 July 2014, a letter from the then Director General of Archives arrived at the Meredith home. Whilst not conceding any mishandling of the matter on the part of Archives, he stated that he would be prepared to return the item to the Chief of Army if he, General Morrison, would accept a claim from Deirdre under the Deceased Soldiers Estates Act of 1918.

Deirdre provided the required proof of kinship, and promptly submitted her claim, which was subsequently accepted by the Army. After some further delays, Lieut. Colonel Malcolm Beck, representing the Australian Army, went to the Australian National Archives in Canberra. There, Richard Moffatt’s ‘disc’ was finally released into the custody of the Australian Army. On 25 September 2014, in an unusual but in a way, fitting act, a Lieutenant Colonel Beck flew to Melbourne specifically to hand the plate to Richard’s descendant, Deirdre, personally. The message from the grave had enabled Richard’s ‘spirit’ to finally return home.

The author is indebted to the Meredith family for permission to quote from their book, ‘Our Only Boy’ which was written by them as a tribute to young Richard Moffat.

Image of Dead Man’s Penny was digitally modified by CONTACT to incorporate Richard Moffat’s name.

.

.

.

.