The RAAC’s First Days: Brian Agnew’s Service

Introduction

‘Baby Boomers’ come from the generation born between 1946 and 1964. I’m one of them. The generation before us is known as ‘The Silent Generation’, born between 1925 and 1945. Many of their families experienced both the Great Depression and the Second World War. The Squadron Sergeant Major (SSM) of my tank squadron in Vietnam was WO2 Brian Agnew. It wasn’t something that I thought about at all at the time, but I know now … he was born in 1932.

If I had thought about it, I’d have assumed that his early life in the military would’ve revolved around pretty much the same things as mine. After all, not much would’ve changed … or would it? When I came to think about it, I realised (it seems obvious now, in retrospect) that the differences were massive. The following account draws attention to the RAAC’s early days; highlighting the experiences of Brian Agnew during that time.

Setting the Scene

“The Defence policy is based on ‘hope’ rather than logic.”

The above is a statement which could easily be dismissed, if it wasn’t for the experience of the person whose view it was … that of the late Lieutenant General Sir Sydney Rowell, KBE, CB; Chief of the General Staff (CGS) from 1950 to 1954. He was referring to contemporary issues, while writing the Foreword to ‘Australian Armour’, in February 1974. [CGS was the equivalent of the Chief of Army today.]

Sir Sydney was proud of the fact that it was during his time as CGS that the decision was made to acquire Centurion tanks to equip 1st Armoured Regiment (which at that time comprised a squadron of Churchill tanks). Many would be unaware that his action in acquiring “the best tank available in any country at the time”, was made easier by the possibility that “a third world war might erupt about the end of 1953”. A surprise to many, I’m sure; but the political and military ramifications of a conflict can never be underestimated, especially if you’re the CGS.

Sir Sydney was proud of the fact that it was during his time as CGS that the decision was made to acquire Centurion tanks to equip 1st Armoured Regiment (which at that time comprised a squadron of Churchill tanks). Many would be unaware that his action in acquiring “the best tank available in any country at the time”, was made easier by the possibility that “a third world war might erupt about the end of 1953”. A surprise to many, I’m sure; but the political and military ramifications of a conflict can never be underestimated, especially if you’re the CGS.

The first Centurions tanks started arriving in 1952. This was later than originally scheduled, priority having been transferred to the 8th King’s Royal Irish Hussars, given their Korean War deployment in late 1950. The level of security concern for the nation was certainly heightened at this time, so much so that steps were taken to raise a 2nd Armoured Regiment in Holsworthy. So it was, that C Squadron, 1st Armoured Regiment, became Nucleus Sqn; getting its first tanks in November 1952. While the Holsworthy Range received its baptism of 20-pounder fire soon after, plans for the 2nd Armd Regt were scrapped in 1955.

Interestingly, at the height of the invasion threat in 1942/43, the Australian Armoured Corps comprised twelve armoured regiments, three armoured car regiments and nine motor regiments … units which were rapidly disbanded following the cessation of hostilities in 1945. It was at this time, that the Interim Army came into being. This was an arrangement by the Government to provide a transitional period between the 2nd AIF disbanding and the formation of the Australian Regular Army (ARA). It lasted from the start of 1946 until mid-1948.

The nation’s security was augmented from 1950 to 1959 by the National Service (NS) scheme introduced at the time. It was fortunate that the order for Centurions had already been placed, as NS imposed considerable pressure on resources; equipment procurement often having to be postponed. The then Citizens’ Military Forces (CMF) role in Australia’s defence, took a back seat at this time as well.

The nation’s security was augmented from 1950 to 1959 by the National Service (NS) scheme introduced at the time. It was fortunate that the order for Centurions had already been placed, as NS imposed considerable pressure on resources; equipment procurement often having to be postponed. The then Citizens’ Military Forces (CMF) role in Australia’s defence, took a back seat at this time as well.

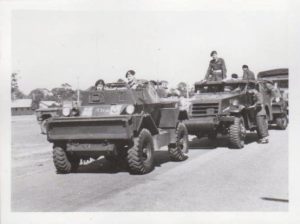

This was especially so for Royal Australian Armoured Corps (RAAC) units. Staghound armoured cars (right) became the mainstay for many; while in tank regiments, General Grants (shown above left) and Matilda IIs were replaced by Centurions, but only to the very limited extent that they could be. Eventually, deliveries from the UK allowed units to receive Ferret scout cars, Saladin Armoured Cars, and Saracen Armoured Personnel Carriers (APCs). Acquiring sufficient tanks to equip the CMF became one of main goals for the armoured corps hierarchy. [The American Staghound had a three-man turret, with a bow gunner sitting to the right of the driver. While its first operational deployment was in 1943, it was still ahead of its time mechanically … having an automatic gearbox and power steering.]

This was especially so for Royal Australian Armoured Corps (RAAC) units. Staghound armoured cars (right) became the mainstay for many; while in tank regiments, General Grants (shown above left) and Matilda IIs were replaced by Centurions, but only to the very limited extent that they could be. Eventually, deliveries from the UK allowed units to receive Ferret scout cars, Saladin Armoured Cars, and Saracen Armoured Personnel Carriers (APCs). Acquiring sufficient tanks to equip the CMF became one of main goals for the armoured corps hierarchy. [The American Staghound had a three-man turret, with a bow gunner sitting to the right of the driver. While its first operational deployment was in 1943, it was still ahead of its time mechanically … having an automatic gearbox and power steering.]

Trooper Agnew, 1RNSWL

Brian Agnew’s introduction to life in the Army came in 1951, when he enlisted in the CMF [which was reactivated in 1948]. At the time, he was finishing a five-year bootmaker’s apprenticeship. Once he’d seen it through, he immediately looked elsewhere. During his two years with 1st Royal New South Wales Lancers (1RNSWL) at Parramatta, he was sent to the Armour School at Puckapunyal for a two-week radio course. This was a positive experience, and, having gained a liking for the life, he decided to enlist in the Australian Regular Army (ARA). [The Armour School was previously known as the Armoured Fighting Vehicle School; later becoming the Armoured Centre. Now it is the School of Armour.]

‘Signing up’ was a straight-forward process and proved to be good timing, as more permanent cadre staff were needed at the Parramatta depot. Joining a WO2 and two corporals, he continued travelling to work from home on the train. He must have been classed as a ‘trained’ soldier, as there was no recruit training to undergo. [1RNSWL linked with 15 Northern River Lancers in 1956 to become 1/15 RNSWL.]

Headdress at the time was black beret, the Australian Armoured Corps (AAC) having gained approval for it to be worn in August 1944. Six months later, approval was granted for the right to wear distinctive silvered badges as per the dress code of the Royal Tank Regiment (and some other Commonwealth armoured corps). The ‘Rising Sun’ was worn universally until unit and Corps badges were produced from 1949 onwards. [The 1 Armd Regt beret badge was not produced until 1955; although smaller collar badges with the Tudor (‘King’s) Crown were available in 1951.]

Headdress at the time was black beret, the Australian Armoured Corps (AAC) having gained approval for it to be worn in August 1944. Six months later, approval was granted for the right to wear distinctive silvered badges as per the dress code of the Royal Tank Regiment (and some other Commonwealth armoured corps). The ‘Rising Sun’ was worn universally until unit and Corps badges were produced from 1949 onwards. [The 1 Armd Regt beret badge was not produced until 1955; although smaller collar badges with the Tudor (‘King’s) Crown were available in 1951.]

While it couldn’t happen now, Trooper Agnew qualified as a Driving and Servicing (D&S) instructor through ‘on the job’ training. The AFVs on which he gained his skills were the Matilda II, the Staghound, the Doodlebug Canadian scout car, and the White Armoured Personnel Carrier (APC). It can be seen how this combination of AFVs could provide the fundamental capabilities for mobile warfare: infantry direct fire support, reconnaissance, and armoured mobility.

While it couldn’t happen now, Trooper Agnew qualified as a Driving and Servicing (D&S) instructor through ‘on the job’ training. The AFVs on which he gained his skills were the Matilda II, the Staghound, the Doodlebug Canadian scout car, and the White Armoured Personnel Carrier (APC). It can be seen how this combination of AFVs could provide the fundamental capabilities for mobile warfare: infantry direct fire support, reconnaissance, and armoured mobility.

Somewhat surprisingly, the 27 tonne Matildas were in good condition, powered by two 95 HP Leyland diesel engines. Interestingly, they had an escape hatch under the driver’s seat, cleverly designed in such a way that didn’t weaken the hull floor. [The Matilda Mark II was a completely different tank to its predecessor.]

Somewhat surprisingly, the 27 tonne Matildas were in good condition, powered by two 95 HP Leyland diesel engines. Interestingly, they had an escape hatch under the driver’s seat, cleverly designed in such a way that didn’t weaken the hull floor. [The Matilda Mark II was a completely different tank to its predecessor.]

Reg Ansett, owner of Ansett Transport Industries, purchased many of the Matildas when they became obsolete; the engines could be easily transferred to his trucks. The A vehicles were supported by an Echelon comprising Blitz wagons and Willys jeeps … still going strong after their Second World War service.

In his assessment for promotion, Trooper Agnew was pleased to discover that he had been rated at ‘3 stars’, the top ranking in the system used at the time. As sometimes still happens today, promotion meant posting and Corporal Agnew was soon to become involved with Army’s top priority at the time — training national servicemen.

In his assessment for promotion, Trooper Agnew was pleased to discover that he had been rated at ‘3 stars’, the top ranking in the system used at the time. As sometimes still happens today, promotion meant posting and Corporal Agnew was soon to become involved with Army’s top priority at the time — training national servicemen.

Come April 1954, he packed his bags for 12 National Service Battalion at Holsworthy; luckily for him there were no tents, new barracks had just been built.

Corporal Agnew, 12 National Service Battalion

Today, it would be known as a ‘corps’ posting. His NS Company was completely made up of RAAC officers and NCOs; while all their recruits were RAAC ‘badged’ (either as a result of earlier CMF service or regional affiliations). Corporal Agnew’s duties required him to provide armoured vehicle familiarisation. Initially he had two Matildas at his disposal, but towards the end of the posting, a Ferret scout car also became available. Interestingly, the Matilda had a preselector gearbox and reservoir containing compressed air (used to power gear changes). [He recalls having to be careful not to let the reservoir run down!]

Today, it would be known as a ‘corps’ posting. His NS Company was completely made up of RAAC officers and NCOs; while all their recruits were RAAC ‘badged’ (either as a result of earlier CMF service or regional affiliations). Corporal Agnew’s duties required him to provide armoured vehicle familiarisation. Initially he had two Matildas at his disposal, but towards the end of the posting, a Ferret scout car also became available. Interestingly, the Matilda had a preselector gearbox and reservoir containing compressed air (used to power gear changes). [He recalls having to be careful not to let the reservoir run down!]

Troop Corporal/Troop Sergeant, C Sqn, 1 Armd Regt

As one would hope, Brian wasn’t forgotten by his Corps career manager and he continued to be panelled for promotion courses and the like. One of these was a 20-pounder gunnery course, his second stint at Puckapunyal. Come August 1956, his next posting order arrived: C Squadron, 1 Armd Regt, Troop Corporal 1 Troop. His troop leader, Lt Terry Walker (just promoted from 2Lt) was regarded as a first-rate officer. [A 1953 Officer Cadet School (OCS) Portsea graduate; he became Commanding Officer (CO) 20 years later.]

Barracks accommodation at that time was in former K-Force buildings. These had been erected when the Government called for volunteers with prior military experience to serve for three years, including one in Korea. The intention was to provide rapid reinforcements for 3RAR who were the first Australian troops deployed to the War (from BCOF Japan).

Ironically, when the Regiment moved to its new accommodation in 1959, it was named Kapyong Barracks, after the 1951 battle involving Canadians and 3RAR [supported by US tanks]. In 1980, the then CO proposed that 1 Armd Regt’s barracks should be named after someone of note from an armoured background. The idea was supported and the late Lt Gen Sir Horace Robertson, KBE, DSO, was chosen; a light horse officer from WWI, who had commanded 1st Armoured Division in 1942.

Little did Brian realise it, but there wouldn’t be much time, initially at least, for crewing tanks. First of all, C Sqn was tasked to mount the guard at HQ Southern Command (Albert Park Barracks). Having finished that, next on the list was providing ceremonial support and security at the 1956 Olympic Games in Melbourne.

The Sqn was accommodated in their own buildings in the Athletes’ Village and had free access to all the large dining halls. Their duty roster was 24 hours on, 24 hours off; providing time to use the buses available to visit event venues.

When contingents arrived from different countries, a small ceremony was held and their national flag was raised (and lowered at the end of the Games). The experience provided an interesting commentary on other countries’ attitudes towards military forces; if soldiers from the Regiment (on duty in uniform) walked towards visitors from other nations, it was not unusual for them to cross over and pass on the other side.

When contingents arrived from different countries, a small ceremony was held and their national flag was raised (and lowered at the end of the Games). The experience provided an interesting commentary on other countries’ attitudes towards military forces; if soldiers from the Regiment (on duty in uniform) walked towards visitors from other nations, it was not unusual for them to cross over and pass on the other side.

One of 1st Armoured Regiment’s squadrons at that time was referred to as the ‘duty squadron’. As well as providing guards and the like, they also undertook many of the vehicle maintenance tasks. Some of the Guards of Honour involved a major effort on the part of the Regiment as a whole. This was the case for the 1954 visit by HM The Queen and the presentation of the Guidon by the Governor General, early in 1956.

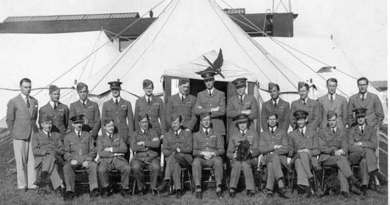

C Squadron’s responsibilities were very different to those of the ‘duty’ squadron. As the ‘operational’ squadron, it was accommodated in tents on Puckapunyal Range and concentrated on perfecting tactical training and battle drills. There were about 50 members of the Regiment with Second World War service at the time, one of whom was Brian’s driver (known as ‘Pop’ because of his age). His gunner went on to be commissioned, later being awarded the Military Cross in Vietnam (Ray Devere).

C Squadron’s responsibilities were very different to those of the ‘duty’ squadron. As the ‘operational’ squadron, it was accommodated in tents on Puckapunyal Range and concentrated on perfecting tactical training and battle drills. There were about 50 members of the Regiment with Second World War service at the time, one of whom was Brian’s driver (known as ‘Pop’ because of his age). His gunner went on to be commissioned, later being awarded the Military Cross in Vietnam (Ray Devere).

One of the other troop leaders, having graduated from RMC in 1955, went on to become CGS: Lt Gen John Coates, AC, MBE. Interestingly, his predecessor as CGS, had been a troop leader in Nucleus Squadron, Lt Gen Laurie O’Donnell, AC. The Recce Troop Leader, Lt D R Kepper (known as ‘Doc’ because of his initials) went on the command the Regiment in 1970. Other young officers at the time, who went on to become CO, were: Latchford (‘69), Bird (‘72) and Jarratt (‘76).

Someone else who rates a mention is Brian’s Squadron Sergeant Major (SSM), the then WO2 Percy White. He was another with Second World War service; service which becomes very interesting when one looks at DVA’s records. Percy was born on 10 Apr 25 and enlisted on 8 Apr 41. One imagines that he concealed his real age. ‘Blancoed’ gaiters, holsters, and belts were standard at the time. [WO1 Percy White, DCM, was RSM, 1 Armd Regt, when the author returned from Vietnam in 1971.]

Someone else who rates a mention is Brian’s Squadron Sergeant Major (SSM), the then WO2 Percy White. He was another with Second World War service; service which becomes very interesting when one looks at DVA’s records. Percy was born on 10 Apr 25 and enlisted on 8 Apr 41. One imagines that he concealed his real age. ‘Blancoed’ gaiters, holsters, and belts were standard at the time. [WO1 Percy White, DCM, was RSM, 1 Armd Regt, when the author returned from Vietnam in 1971.]

Promotion to sergeant is always something to remember. In Sgt Agnew’s case, WO1 Arthur King was the RSM and Brian recalls that he was immediately appointed messing member on the Sgt’s Mess Committee. [King was 1 Armd Regt’s longest serving RSM: doing four and a half years in the role.]

Radio Wing Sergeant Major (WSM), Armoured Centre

When he became aware of a shortage of ‘schools’ instructors, Sgt Agnew volunteered. So it was, that he was nominated to do a radio instructors’ course (he would also have been content to do either gunnery or D&S). A recollection from the then Captain Colin Toll [CO, 1 Armd Regt,1979]:

“In 1966, I had just returned from Malaysia and Borneo, was newly promoted, and posted as OC Radio Wing. These were busy times with conscription underway and the Vietnam war ramping up. The WSM was WO2 Brian Agnew. As he was very much my senior in age, wisdom and experience, I let him lead and educate me. I have always had a great respect for our soldiers, especially senior non-commissioned officers. Brian was a very fine example.”

[The author was one of those who directly benefited from WO2 Agnew’s expert teaching; having completed a radio course in 1969.]

SSM of a Tank Squadron on Active Service

Brian was appointed SSM, C Sqn, 1 Armd Regt, in late 1969. The squadron spent the following 12 months training for Vietnam: tents at ‘Nui Dat 2’ on Puckapunyal Range became their home; a specially built command post closely resembled that used by the squadron in Vietnam (in which the ‘duty officer’ slept); and maps were overprinted with Vietnamese names. As 1971 approached, he left a month early as part of the squadron advance party. The year on operations proved how fortunate the OC was to have an SSM who supported him fully, while at the same time being dedicated to the welfare of his soldiers. Someone respected by all.

Brian was appointed SSM, C Sqn, 1 Armd Regt, in late 1969. The squadron spent the following 12 months training for Vietnam: tents at ‘Nui Dat 2’ on Puckapunyal Range became their home; a specially built command post closely resembled that used by the squadron in Vietnam (in which the ‘duty officer’ slept); and maps were overprinted with Vietnamese names. As 1971 approached, he left a month early as part of the squadron advance party. The year on operations proved how fortunate the OC was to have an SSM who supported him fully, while at the same time being dedicated to the welfare of his soldiers. Someone respected by all.

This included the Squadron Second in Command (2IC) who had met first Brian under very different circumstances. Trooper John Scales had enlisted in the Army in 1959 and was allocated to Armoured Corps after recruit training at Kapooka: “I clearly recall being told to report to Corporal Agnew, who quickly organized me and settled me in.” To young Trooper Scales, Cpl Agnew left his mark as one who “was highly respected and influential — in his own quiet way”. Twelve years later, Trooper Scales had become Captain Scales after completing 12 months at OCS Portsea in 1960. In 1970 he was OC of an APC Troop in Vietnam. As sometimes happens in the Army (or large corporations), the need arose for a 2IC of the tank squadron to be appointed ‘in country’… so it was, that Capt Scales was swapped, reluctantly on his part, from A Sqn, 3 Cav Regt, to C Sqn, 1 Armd Regt. He recalls that it was “a great relief to find that Brian Agnew was the SSM”.  Furthermore … “I doubt if I would have survived the transition [not having trained together for 12 months beforehand as everyone else had done] without the support and advice of Brian Agnew. I cannot think of a time when his advice was wrong.”

Furthermore … “I doubt if I would have survived the transition [not having trained together for 12 months beforehand as everyone else had done] without the support and advice of Brian Agnew. I cannot think of a time when his advice was wrong.”

Being the last tank squadron deployed, it fell to C Sqn to clean the tanks and prepare them for return to Australia. As they were too heavy for the ship’s cranes, engine decks, transmission covers, and barrels had to be removed. It was somewhat of an understatement to say that SSM Agnew (pictured leaning forward) and the Sqn OC, were pleased when loading was complete.

Long Term Schooling, UK

The first posting order Brian received for 1972, was to RMC; but soon after, a letter arrived from the Australian Army Staff in London. Good news … he had been chosen as the Australian student (only one selected annually) to attend a series of training courses at the Royal Armoured Corps (RAC) Centre in Dorset, UK. There were five courses in all: radio, guided weapons, proof and experimental, long gunnery, and long D&S. At the end of all this, he was attached to the RAC Centre’s Signals School as an instructor. Before returning to Australia, his name was added to the RAC Centre Honour Board, a lasting acknowledgement of the excellent results he’d achieved and the contribution he’d made.

The first posting order Brian received for 1972, was to RMC; but soon after, a letter arrived from the Australian Army Staff in London. Good news … he had been chosen as the Australian student (only one selected annually) to attend a series of training courses at the Royal Armoured Corps (RAC) Centre in Dorset, UK. There were five courses in all: radio, guided weapons, proof and experimental, long gunnery, and long D&S. At the end of all this, he was attached to the RAC Centre’s Signals School as an instructor. Before returning to Australia, his name was added to the RAC Centre Honour Board, a lasting acknowledgement of the excellent results he’d achieved and the contribution he’d made.

Armoured Centre

On return to Australia in late 1973, he was posted to the Armoured Centre, as the Senior Assistant Instructor; a position which provided the latitude to oversee and supervise instruction in all courses and at all levels; an ideal role in which to disseminate his new knowledge and learning. The CO was known to him: Lt Col ‘Jack’ Chipman, one of the C Sqn troop leaders from 1956.

On return to Australia in late 1973, he was posted to the Armoured Centre, as the Senior Assistant Instructor; a position which provided the latitude to oversee and supervise instruction in all courses and at all levels; an ideal role in which to disseminate his new knowledge and learning. The CO was known to him: Lt Col ‘Jack’ Chipman, one of the C Sqn troop leaders from 1956.

The RAAC Corps Director at the time was Col ‘Blue’ Keldie, MC. On a visit to Puckapunyal, he made a point of catching up with Brian … to tell him that he was to be promoted WO1! There was to be another surprise to come.

The first awards in the new Order of Australia were announced as part of the 1975 Queen’s Birthday Honours. Procedures have since changed; however, for him … it was a total shock! The evening before, he was told to be sure to check the paper the following day. He had no idea why.

Next morning he discovered that he’d been made a Member of the Order of Australia. There was to be a delay before he could be invested, however. Her Majesty requested that she be the one to preside over the first investitures of the Order, as part of her forthcoming Silver Jubilee Tour. As it happened, he and his family wouldn’t have very far to travel to Government House, Canberra … to meet the Queen.

RAAC Directorate, Army Office, Canberra.

Brian’s next posting (1977) provided further opportunity for his broad knowledge of all things armour, to be put to good use. It was his first posting to Canberra (Campbell Park Barracks); a place which was to become home for the family. Quickly settling in, he was to remain at the Armoured Corps Directorate for the next five years.

Brian’s next posting (1977) provided further opportunity for his broad knowledge of all things armour, to be put to good use. It was his first posting to Canberra (Campbell Park Barracks); a place which was to become home for the family. Quickly settling in, he was to remain at the Armoured Corps Directorate for the next five years.

The day of his investiture was fine, the trip to Government House just a little daunting. When the moment arrived for his presentation to be made, he was comforted by a wink from the Queen’s Equerry. It happened to be Lt Col Peter Badman, RAAC. [He’d been the OC of the first tank squadron to serve in Vietnam in 1968 and was known to Brian.]

One of his tasks at the Directorate, tested his memory from 25 years earlier. An RAAC officer on the staff at nearby RMC telephoned him ‘on the off chance’ that he might be aware of an AFV of some sort in the vicinity. As it happened, Brian knew of a Ferret which, surprisingly, was still a ‘goer’. The enquiry had been made because, on a particular day just prior to graduation, the RMC cadets were allowed to go on parade in a way that reflected the corps into which they were graduating. Having passed on instructions on the phone as to how to drive it (Brian’s explanatory skills were as good as ever), the Ferret was brought to Canberra and the RAAC graduating cadets ‘stole the show’ by driving it onto the parade ground for their special day.

Commissioned

Captain Agnew didn’t have to pass a commissioning course in 1983. Being in the first batch to be commissioned ‘from the ranks’ … there was no course! His first appointment was to ‘Local Admin’, at Army Office in Canberra. A lot of the work involved responsibility for managing and acquitting the copious amounts of money involved with pay.

Come 1985, there was yet another surprise in store. He must have been doing something right, as his new responsibility was to be Admin Officer for the annual UK/Australia exchange, Exercise Long Look. This involved almost five months in the UK co-ordinating arrangements in which about 100 Australian soldiers across a range of different Corps and ranks, serve in individual jobs with their British counterparts. The exchange had been operating since 1976, nevertheless, there was always a requirement for someone to be on-hand to sort out any problems, should they arise. As things happened, nothing untoward arose and the flights there (on RAAF 707) and back (on RAF VC 10) were without incident … leaving just a little time for sight-seeing.

Come 1985, there was yet another surprise in store. He must have been doing something right, as his new responsibility was to be Admin Officer for the annual UK/Australia exchange, Exercise Long Look. This involved almost five months in the UK co-ordinating arrangements in which about 100 Australian soldiers across a range of different Corps and ranks, serve in individual jobs with their British counterparts. The exchange had been operating since 1976, nevertheless, there was always a requirement for someone to be on-hand to sort out any problems, should they arise. As things happened, nothing untoward arose and the flights there (on RAAF 707) and back (on RAF VC 10) were without incident … leaving just a little time for sight-seeing.

While the Exercise was in progress, he received advice that the RAAC Corps Director and an accompanying officer would be in London prior to attending a Quadripartite Working Group on Armour; he arranged to meet them. [The officer with the Director happened to be the author.]

Major Agnew left Army Office for Defence Central in 1986. A Lt Col had recently retired and the position had to be filled … so it was that he was promoted and became eligible for higher duties allowance. Brian’s responsibilities involved taking the initiative, as liaison officer, for gathering information relating to the environmental impact of Defence sites (and proposed sites) in the Northern Territory.

He would examine the circumstances on the ground and report back to Defence on his return to Canberra. One of the early sites on his ‘watch’ related to RAAF Base Tindall, near Katherine; other locations included Weipa and Cobourg Peninsula (Arnhem Land).

The retirement age for a major was 55, meaning that he had only a couple of years left … there are always exceptions, however. Brian’s service was extended on two occasions, because of the essential nature of the work he was doing.

Department of the Senate

He finally retired from the Army in Dec 1989, a career spanning 38 years. But he was still a ‘young’ 57, where to next? There were vacancies in the department which provides secretariat support for the Senate and Brian’s application was successful. Starting out as part of the security staff, he later became an attendant in the Chamber, and finally, a member of the team supporting the estimates committees.

In 1996, he’d been with the Senate for seven years. It was then that he had his heart attack. The air ambulance got him to St Vincents Hospital in Sydney; one operation, but it involved four by-passes. As ever, he’d provided reliable and diligent service while with the Senate. Who knows whether or not it was in acknowledgement of this, that he was granted a redundancy package.

In 1996, he’d been with the Senate for seven years. It was then that he had his heart attack. The air ambulance got him to St Vincents Hospital in Sydney; one operation, but it involved four by-passes. As ever, he’d provided reliable and diligent service while with the Senate. Who knows whether or not it was in acknowledgement of this, that he was granted a redundancy package.

Volunteering

Maybe it was the fact that he’d never been a drinker or a smoker that contributed to his speedy recovery. Brian was always one to see opportunities and now a big one appeared … that of helping others in need. Some years ago, the Government of the ACT oversaw the establishment of what have now become three community-based Veterans Support Centres (VSC).

Their role is to help serving and former Defence Force members and their families with claims to the Department of Veterans’ Affairs, as well as helping with welfare matters. Brian is a life member of the VSC at Page. His help might only be with the BBQs and the food van; but it is a contribution. Putting back something in return for what he’d been lucky enough to receive over the years.

Their role is to help serving and former Defence Force members and their families with claims to the Department of Veterans’ Affairs, as well as helping with welfare matters. Brian is a life member of the VSC at Page. His help might only be with the BBQs and the food van; but it is a contribution. Putting back something in return for what he’d been lucky enough to receive over the years.

Conclusion

At a time when, after 75 years’ service to the nation crewing tanks, the Chief of Army has decided to remove 1 Armd Regt from the Order of Battle and give it a different role as a non-combatant, it is worth reflecting on a time when members of the Regiment gave their all to meet the Army’s needs. Writing in the 1955 regimental journal ‘Tracks’, Brigadier Murdoch, CBE, explains that “The Regiment, in addition to preparing as a unit of the field force for possible operational tasks, has training responsibilities in regard to the corps, as a whole”. These duties involved (amongst others) training all RAAC recruits, as well the selection and training of NCOs for appointments both inside and outside the Regiment. He went on to say: “It is clear then that the general efficiency of the RAAC depends in no small measure on the success achieved by the Regiment in the many tasks allotted to it”.

The final words of the then CO, Lt Col Kit Miles, in the Journal are ironic, given the present circumstances. Having earlier pointed out that “We are virtually the hinge pin of the Armoured Corps as a whole”; he finished by adding: “The Regiment has much to be proud of in its past, but its future depends both on ourselves and upon circumstances that we cannot control. So let us strive to go forward to a future that, in later years, we shall be pleased, and proud, to call our past”.

I, for one, am proud to know Brian and am honoured to have had the opportunity to record the story of his outstanding service. What an example they are to us … all those who serve and contribute to the betterment of the RAAC, as Brian Agnew has done! What a proud heritage we have!

Brian’s advice to those joining today … “Have an aim, something you want to achieve.”

In his case, Trooper Agnew said to himself, “I’d like to do that one day!” … referring to the then WO2 Arthur King who had just returned from the RAC Centre in the UK and who had been his radio instructor in 1952 when he did his first course at Puckapunyal.

In the words of a colleague: “Brian was one of a kind, a great soldier and with lots of knowledge. Respected by all who came in contact with him”.

- ‘Australian Armour: A History of the Royal Australian Armoured Corps 1927 – 1972’; Major General R N L Hopkins, CBE; Australian War Memorial and the AGPS; Canberra; 1978.

- Originally, Australia ordered over 500 Churchill tanks. This number, however, was cut back as the threat of Japanese invasion passed. Eventually, 51 were delivered after the end of the War.

Lieutenant Colonel Bruce Cameron, MC, RAAC (Ret’d)

Images supplied by the author

.

.

.

.

Brian and I lived next to each other in quarters in Puckapunyal. Always a Gentleman.

Nice to have known him.

Major Grantley Kemble mid

Retired Military Gentleman