|

|

|

Reg

Boys [third from left] and colleagues prepare for a mission

|

Bomber

Command

Of 32 VCs awarded to the RAF in WWII, 10 went to Lancaster crew

members

125,000

aircrew served in Bomber Command

47,000 were killed in action

9800 were taken POW

3486 Australians KIA

724 Australians killed in training

|

Bomber

Boys

Bomber

Command absorbed just 2 per cent of Australia's young men committed to

fight in World War II but accounted for 20 per cent of her total loss

of life in the conflict - 3486 killed in action. Flt-Lt Reg Boys DFC was

among those who survived to tell his tale.

WORDS

BRIAN HARTIGAN PHOTOS SUPPLIED BY REG BOYS

RAAF's No

467 Sqn, with a full-strength compliment of about 140 aircrew, recorded

almost 800 casualties in just 28 months - replacement and reinforcement

barely able to keep ahead of the statistics. Of the 590 men killed in

action in this one squadron alone, five were commanding officers.

Confident

in the strength of his European defences early in the war, Herman Goering

assured his Commander-in-Chief, Adolf Hitler, "No enemy plane will fly

over the Reich territory". In defiance of this boast and with a statistical

average life expectancy of just 13 sorties, Sydney-sider and navigator

Reg Boys flew a remarkable 40 operational sorties over enemy territory

- 11 of them over the very heart of the Reich - Berlin.

After completing

his training in Australia, Canada and England, Reg Boys was posted to

RAAF's No 467 Sqn as a navigator on Lancaster heavy bombers in June 1943.

Over the course of the next eight months, Reg flew three more than his

required 30 operational sorties before transferring as an instructor to

27 Operational Training Unit.

A little

more than a year later he was back with 467 Sqn and completed a further

seven raids over Reich territory before peace was declared.

Reg's flying

career started on home soil with basic pilot training in Victoria and

New South Wales on Tiger Moth aircraft. Recategorised as a navigator,

he was shipped off to Winnipeg, Canada where he was among the first intake

of navigators from across the Commonwealth to be trained in that country

- on Anson aircraft.

|

|

|

Reg

Boys [third from left, front row] and his graduating class, Canada,

1943

|

|

|

|

Reg

Boys DFC reflects on a distinguished flying history

|

Still on Ansons,

further training followed in England and Wales before he was eventually

invited to join a team.

"A bloke

by the name of 'Buck' Jones said he liked my training record and wanted

me to help him form a crew," Reg says.

From these

beginnings, a tight-knit crew was drawn together and began the next phase

of training on the bigger, faster Wellington bomber.

Remarkably,

it was during this phase of his long flying career that Reg had his most

serious flying mishap and, as these things go, it was rigorous training

that probably saved his life.

"One thing

we trained hard at as a crew - in our own time - was abandoning the aircraft.

We figured that if we practiced often enough, the training would kick

in and you would do the drill automatically even if you were concussed

or something.

"Well, wouldn't

you know it, one day on a training mission, a prop fell off our Wellington

at about 1000ft - and those things were lucky to fly with two good engines.

So we had to bail out quick smart."

The experience

brought the men much closer together. So much so in fact, that the crew

evolved into a dynamic, democratic small team.

"There was

no such thing as a captain in our aircraft, except for takeoff and landing

- or if we ever had to abandon again.

"There was

no speaking on our plane either, unless it was necessary for the mission.

We always kept the airways clear in case of emergency.

"It was a

good piece of training that helped keep a professional, one-unit kind

of atmosphere that was very important to us."

Heading into

the final stages of training - conversion to heavy bombers - brought the

first real opportunity to talk to men who had already flown on operations.

And, in fact, one of these experienced men passed on that one small piece

of advice that Reg credits with his survival through the next three years

of war.

Encouraged

by this instructor, Reg and his crew developed a method of operation that

required an extra level of attention to navigation.

During their

transit flight from takeoff to an attack initiation point, heavy bombers

were vulnerable to predatorial German fighters. They were also virtually

free to travel as they pleased to the predetermined form-up point over

the Continent before advancing on their target. Yet most crews flew the

big bombers "by the book" - straight and level.

"I was always

a bit concerned about the notion of bombers flying along straight and

level in large groups. It seemed to me they were making good targets of

themselves.

"In fact,

the Germans even had some fighters configured with their guns pointing

up at an angle so they could just cruise around under the bombers and

hose their bellies."

|

|

|

“That’s

me [left] and Wing Commander Ian Hay with the only Aussie POW we

flew out of Germany on 7 May 1945” – Reg Boys

|

So, Reg's crew

broke from the norm and followed their own zig-zag route to an attack initiation

point, tacking like a ship at sea, which apart from making their route less

predictable, also offered the gunners a valuable opportunity to sweep their

blind spots during each turn.

Despite the

success of this tactic, Reg was a little reticent to pass on his technique

however.

"It's not

that you wanted to keep it from your mates - but you didn't want the powers

that be hearing about it either. There was always the fear that you'd

be ordered to conform.

"At the end

of the day, though, no matter what they told you, once you were in the

air you did your own thing anyway."

A typical

operational day for a bomber crew could last up to 15 hours from the time

they reported for briefings until they brought their aircraft home.

A bombing

raid over Reich territory was an awesome thing. As many as 1000 heavy

bombers taking off in waves, five minutes apart, from numerous bases across

southern England, each carrying an almost seven-tonne bomb load.

For the individual

crews, the Lancaster was not the most comfortable mode of transport. Although

the cabin had some heating, icy drafts from many orifices and joints blew

through the fuselage, which itself was a single thin skin of aluminium

holding out freezing temperatures - and frostbite was not uncommon. Crew

discomfort was added to as low air pressure and a sustaining pre-flight

meal combined to produce internal winds of a more personal nature.

Reg Boys

and his fellow navigators were responsible for getting the bomber to the

target area, after which it was the bomb aimer's job to drop the payload

onto the actual target. Factoring in a myriad variations, and when completely

satisfied of hitting the target, the bomb aimer pushed his release button.

Rather than drop all at once, however, pre-programmed machinations in

the bomb bay saw the various bomb types fall to earth at intervals designed

to see them reach the ground at the optimum spacing for maximum effect.

Getting to

or away from the target area was not easy - the crews gambling their lives

on each occasion. Reg says the flack was so thick some times he often

imagined they could land on it. But, thankfully, they always seemed to

be able to fly above it.

|

|

|

Reg

Boys [left] and W. Wilkinson [later killed in action] sit atop a

4000lb Block Buster bomb

|

|

Lancaster bombers were…

First to fly pathfinder missions – Aug 1942

First to carry 8000lb bombs – Apr 1943

First to carry a 12,000lb bomb – Sept 1943

First to carry 12,000lb deep penetration bomb – Jun 1944

First to carry 22,000lb Grand Slam bomb – Mar 1945

Of

7374 Lancasters built, 3400 were lost on operations plus another

200 destroyed in crashes

Weight

Empty 37,000lbs (16.8tonne)

Loaded 65,000lbs (29.5tonne)

Performance

(loaded)

Speed 275mph

Cruise 200mph

Range 2530 miles

(with 7000lb load)

1660 miles

(with 14,000lb load)

Fuel

(100 Octane) 2154 gallons

Armaments

8 x .303 Browning machineguns

|

|

|

|

Reg

Boys [seated on bonnet] talks to former POWs before flying them

home to England onboard S Sugar

|

S

for

Sugar - Lancaster Serial Number R5868

Flew 137 operational sorties

Wing span 102ft

Length 69ft 6in

Height 20ft 6in

Engines

4 x rolls Royce Merlin MkXX - Later replaced by Merlin Mk 22

1480 horse power each

|

|

|

|

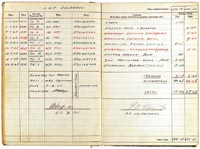

A

sample of Reg Boys’ meticulous record of operations over Reich

territory, including two flights aboard S for Sugar

|

Barely a mission

went by that someone didn't come home, however, and, oddly, according to

Reg, it was the people on the ground who seemed to feel the loss most.

The ladies

in the kitchens seemed hardest hit. It was their duty to feed the men

before and after a mission.

Each aviator

was rationed in for one egg after his flight and to keep tabs on how many

eggs to cook, the kitchens were tuned in to the control-tower radios.

So it was that the cooks heard first-hand whom of the men they had fed

just hours earlier would miss out on the one little luxury afforded them

despite the general rationing across the country.

The truck

drivers who ferried crews to and from the flight line and the mechanics

who looked after their aircraft also felt the loss.

Ground crew

were assigned to individual airplanes and were as much a part of the aircraft's

extended family as the men who flew it.

Reg and his

crew were presumed lost one night when they had fuel problems and had

to land at another airfield overnight and had missed a meal.

"When we

got back to base the next day, there was this amazing feeling among the

dozens of people who came out to greet us - there was almost a family

relationship between everyone."

The closest

Reg recounted coming to actual grief was on one mission when, shortly

after departure, the cabin began to fill with smoke. As with most aircraft

immediately after takeoff, the plane was far too heavy to attempt a safe

landing. Setting a course for The Wash - an area of sea off the English

east coast - to dump their bombs, Reg then assisted all available crew

to search for the source of the smoke.

Unsuccessful

in finding any fire, the captain decided to press on for Dusseldorf -

this night's target.

In the confusion,

Reg had not followed his charts and it took some time to get his bearings

in the blackness of the night. No sooner had he satisfied himself of where

exactly they were than the aircraft was locked in the converging beams

of several searchlights - an occurrence as dangerous as it was unnerving.

"Corkscrew

starboard," a gunner called out. The pilot immediately threw the sturdy

Lancaster into an evasion manoeuvre the crew had discussed and practiced

many times. Inputting full aileron control to turn the wings vertical,

then kicking in full bottom rudder, the heavily laden bomber entered a

vertical dive before pulling out in a corkscrew turn at the bottom - successfully

shaking the attention of the lights.

The Lancaster

was a pretty big airplane to throw around the sky like that, but Reg says

she could handle it.

"The pilot

would never pull a stunt like that without asking first or without the

call from the gunners or someone else, however.

"That's how

much of a crew we were - a unit."

On another

occasion, Reg remembers the confidence of his training kicking in to again

possibly save his comrades.

Europe and

England was pretty dark at night because of the blackouts. Navigation

was assisted by pathfinder bombers who dropped marker flares at mission-designated

points to give navigators a fix.

"One night,

coming home from Berlin, I had no sooner said, "We should be seeing the

markers any minute now" than the pilot spotted it way off to our left."

"Should we

fly to it?" the pilot asked.

"No, let

me make a check - no, I'm sure the PFF [pathfinder flight] have made a

blue - they've dropped the markers north-west of the wrong town."

"Are you

sure?" the anxious pilot demanded.

"Just keep

an eye out to port. If I'm right, those other guys will cop the flack

over the islands in about four minutes.

"And sure

enough, just on four minutes later, the sky off to our left lit up with

a barrage of flack."

Rather than

bask in his own sureness, however, Reg joined in a silent vigil as the

crew rode, mentally, through the barrage with their unseen colleagues.

Reg says

a quiet prayer never went astray.

"I figured

there must be someone out there looking out for us and I was never afraid

to say a quiet prayer before takeoff.

"But I was

never one for leaving things to luck.

"Some guys

seemed to live in the moment, but I always had a mind to the next night

and the night after that.

"I remember

one crew that was having a hell of a party one night and the next night

they went missing. Now, whether the two were connected or not you couldn't

tell - or were they just unlucky.

"I didn't

like to leave anything to luck, and that was the way our crew always worked,

and we survived to tell about it."

But lady

luck can deal her cards against you despite well-intentioned planning.

"One night

we swung on the runway - twice - with a full load of bombs on board.

"S Sugar

had lost half a wing on a mission and this was her first flight back after

repairs and her controls were a little out of balance.

"It was a

hairy experience, but we eventually got her off the ground, got the job

done and got her home again."

S for Sugar,

in which Reg logged 14 flights, is one of England's most respected and

loved bombers (like our own G for George), today lovingly restored and

on display at the RAF Museum, Hendon.

Lancaster

bomber serial number R5868 was built in 1942 and commenced service with

RAF's No 83 Sqn. Known then as Q for Queenie, she completed a not-insignificant

68 operations.

No 467 Sqn,

Royal Australian Air Force, was raised at Scampton, Lincolnshire, on 7

November 1942, moving a month later to Bottesford, Leicestershire - and

commenced operations in January '43. Q for Queenie was allocated to B

flight of the squadron and renamed S for Sugar.

She went

on to war's end, finally clocking up a remarkable 137 operational sorties

before No 467 Sqn was disbanded in September 1945.

|

|

|

“By

Jove, home at last” – crews customising their aircraft

for Operation Exodus

|

On 7 May 1945,

Reg Boys, navigating for squadron OC Wing Commander Ian Hay, flew on Sugar's

final mission - a "cook's tour" of German cities to observe the effects

of bombing raids and to assess the suitability of certain airfields to accept

heavy aircraft.

"We nearly

didn't take Sugar on that flight," Reg says, "She was down for repairs.

But I said to the OC the day before that if he told the maintenance boys

where we were taking her, they would see she was ready.

"And sure

enough, I think they worked through the night to send her on her last

sortie" - Right into the heart of the Reich territory.

|